The United Nations’ AIS Big Data Hackathon in September attracted entry applications from many global organisations and academic institutions. Only 17 applications were accepted; 16 world-ranked research institutes and leading universities plus one corporation – Wärtsilä. And it was Wärtsilä who ended up winning.

The UN event was aimed at developing innovative and viable means for utilising big data to combat either the COVID-19 pandemic or climate change. The participants could choose which of these challenges to tackle, but the first challenge was to be accepted as a participant. Wärtsilä was the only corporate applicant to be asked to take part. As Wärtsilä’s team leader Thomas Dewilde put it: “In sporting terms it was a bit like qualifying for an Olympic final. Just getting there had been a tough fight, and it was an honour to be standing next to the others on the starting line, all of whom are world-class performers. So, winning the gold medal – or in this case the UN competition – was an unforgettable triumph.”

Wärtsilä opted to address climate change. The company has for years demonstrated its commitment to reducing the maritime sector’s carbon footprint through innovative technological solutions. In 2017, Wärtsilä published its Smart Marine Ecosystem vision, which emphasises the use of digital technology and connectivity to raise efficiency levels and reduce environmental impact. Considering this, and since the company’s stated purpose is to support sustainable societies with smart technology, the climate change challenge was in many ways an obvious choice.

Enabling more accurate emissions policy making

The central focus for the Wärtsilä team, named ‘Blue Carbon’, was to upgrade the reporting accuracy for ship emissions by breaking them down geographically. For example, quite recently the fourth IMO Greenhouse Gas Study was published, which showed that the level of emissions occurring within national waters, as opposed to international waters, had been previously understated. Thus, by identifying both the geographical concentrations and the build-up over time of CO2 emissions from shipping, Wärtsilä concluded that environmental policy making could be based on accurate factual evidence, allowing greater input from national and regional authorities to support the IMO’s regulatory efforts.

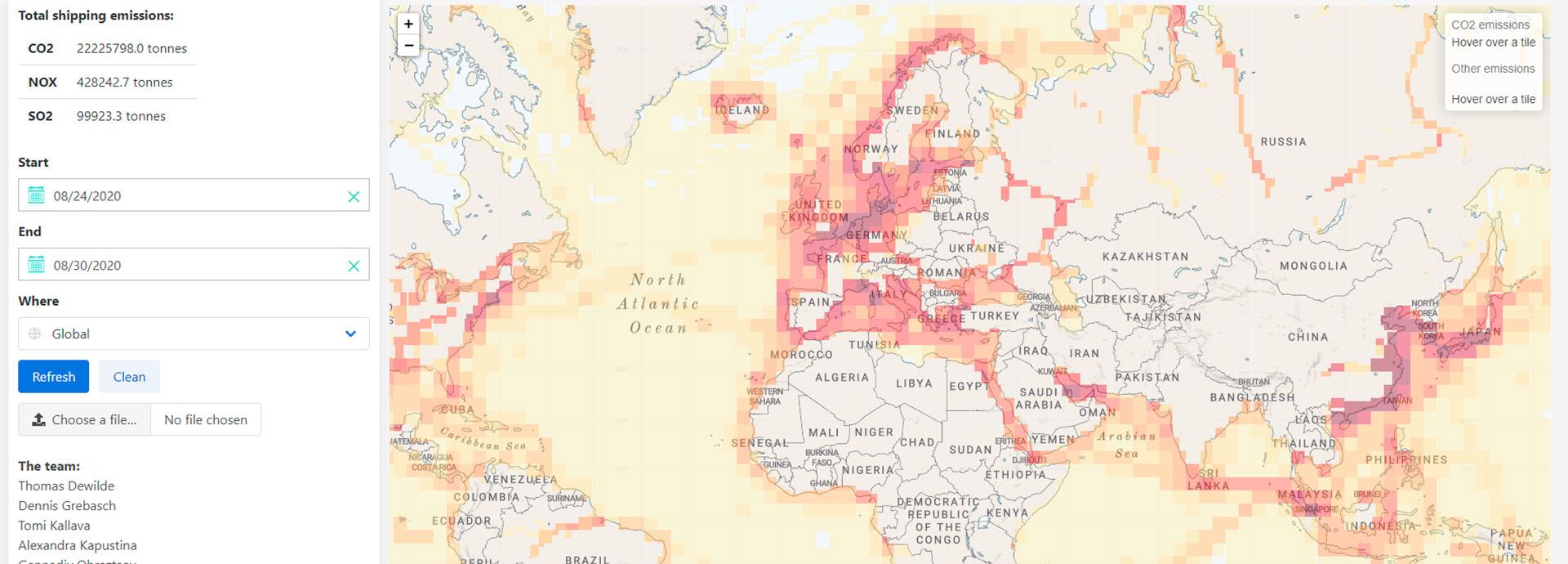

To do this, the team came up with an innovative way to utilise the positional data for ships that is available via the industry’s Automatic Identification System (AIS). A model was developed that makes it possible to attribute the CO2 emissions from ships to the locations where they originated. This supported the creation of a global map providing a comprehensive picture of the true state of maritime emissions. Not only can this map aid regulatory development for shipping, it can also help research institutions to attain greater accuracy in their measurements by using this data to eliminate emissions generated by ships. This will enable them to deliver more detailed studies of emissions from coastal sources or biogenic origins.

Shipping lanes and areas of high emissions are revealed at a granular level

Shipping lanes and areas of high emissions are revealed at a granular level

In Alignment with Climate TRACE

The model developed by Wärtsilä enables close alignment with, for example, the work of Climate TRACE, a coalition of nine climate and technology organisations headed by Al Gore, the former Vice President of the United States. The coalition’s aim is to utilise satellite data, artificial intelligence, and other technology to track greenhouse gas emissions from across the globe remotely.

The current problem identified by Climate TRACE is that emissions data are produced by local governments and authorities and collated at a national level. This means that the validity of the data can vary significantly from country to country and from region to region. By creating a system that delivers a single reliable set of data, countries would be able to verify that their counterparts are following through on emission reduction commitments, and regulatory bodies such as the IMO would be better positioned to enforce the rules.

“Since 2018 it has been mandatory for ships sailing to and from European ports to report their annual emissions. The IMO has required the same for all vessels globally since 2019, but unfortunately this information is not made public. So, in that sense, we are not so far away from Al Gore’s vision,” noted Dewilde.

Increases in regulatory restrictions and related policy making are inevitable, and the model developed by the Wärtsilä team for the UN Hackathon can play a significant role in ensuring that future decisions are based on fair and reliable information.

EU carbon initiative will benefit from real-time emissions tracking

The EU’s emissions trading system is a cornerstone of the EU’s policy for combating climate change and its key tool for reducing greenhouse gas emissions cost-effectively. A cap is imposed on the total number of emissions allowed from any installation, and within the cap companies receive or buy emission allowances which they can trade with one another as needed.

Both Climate TRACE and the recent decision by EU lawmakers to include shipping emissions in the EU carbon market show that increased transparency is inescapable for the shipping industry. Increases in regulatory restrictions and related policy making are inevitable, and the model developed by the Wärtsilä team for the UN Hackathon can play a significant role in ensuring that future decisions are based on fair and reliable information.

Wärtsilä’s contribution, both in its product development strategy and this use of big data to deliver accurate vessel emissions data, supports the UN’s ambitions in a concrete and easily definable way.

Recently the United Nations celebrated its 75th anniversary, and the Hackathon event highlighted the organisation’s increasing focus on lessening the impact of climate change as part of its peacemaking efforts. Wärtsilä’s contribution, both in its product development strategy and this use of big data to deliver accurate vessel emissions data, supports the UN’s ambitions in a concrete and easily definable way.