One of the many things HIFK head coaches, Jarno Pikkarainen of the men’s team and Saara Niemi of the women’s team, agree on it is that constructing a championship-contending team begins with understanding human personalities and perfecting teamwork. Read on to know more.

In ice hockey – as in any other team effort, whether it takes place on ice, hardwood or on an office floor – the creation of a contending team begins with training individual personalities to work towards a shared goal. For instance, in Helsinki’s hockey team HIFK, various personality types are considered essential ingredients with everyone allowed to be themselves.

“Team building begins with selecting the right individuals. People need to feel safe and be allowed to be who they are. After that comes everything else,” explains Jarno Pikkarainen, the coach of HIFK men’s team.

Some characters are more laid back. Others are vocal charismatic leaders. At times, some athletes achieve the rare status of a local hero, like Marko “Mörkö” Anttila did. At times, some achieve the even rarer status of a global hero, like the retired NHL star Teemu Selänne.

“At best, these types of mythical leaders can be important vanguards and provide a team with essential experience on how to approach and include teammates,” feels Pikkarainen. “That is if the image of them as heroes is actually based on reality. Some of these hero characters can also be myths created by the media, and those myths don’t always resonate with the actual situation.”

It’s always a delicate game for a coach to balance the egos of individual players and align it to the team’s mutual goal. Pikkarainen knows that young athletes strive to prove themselves every night in the rink, and with international scouts always on the lookout for fresh talent, sometimes the urge to put one’s individual success ahead of the team’s might be strong.

“Sometimes younger players might have unrealistic expectations of their own abilities. But the best ones always understand that playing for the team makes the individual look good as well. When this understanding is achieved, there are no conflicts of interest,” he says.

Out of balance

Meanwhile, when it comes to the HIFK women’s team, also known as Stadin Gimmat, the case is a bit different. Their head coach Saara Niemi says that while there are scouts and professional leagues out there looking for new players, the amount of money involved in women’s hockey is marginal compared to men’s hockey. In Finland, there are no salaries for players, but financially, HIFK is, in fact, one of the best organisations for women to play.

“We provide an exceptional privilege since our players don’t have to pay for their license. In many teams they do. Our foreign players are also accommodated by the organisation,” explains Niemi.

However, the compatibility of personalities is as crucial in women’s hockey as it is in men’s hockey, and to ensure this, Stadin Gimmat has hired a mental coach. This differs from Pikkarainen’s approach, where he believes that the mental and physical aspects of coaching shouldn’t be separated from each other. In the men’s team, if a player needs special attention, he has the ability to schedule meetings with a sports psychologist, but the team hasn’t hired a designated mental coach.

That said, Niemi believes that the social chemistry within a women’s team works a bit different from men, making their choice a natural one.

“I’ve noticed that men often say it out loud to each other if something bugs them, whereas women keep the problems inside, and it might develop into something bigger in time. That’s why coaches have to be involved in maintaining chemistry,” she says.

Coaching from the rink

While Hockey is a team effort, first and foremost, the coach has to be the leader of the pack. The concept of leadership has evolved over the years, but Pikkarainen and Niemi both share the view that you can’t force yourself into being “one of the guys”.

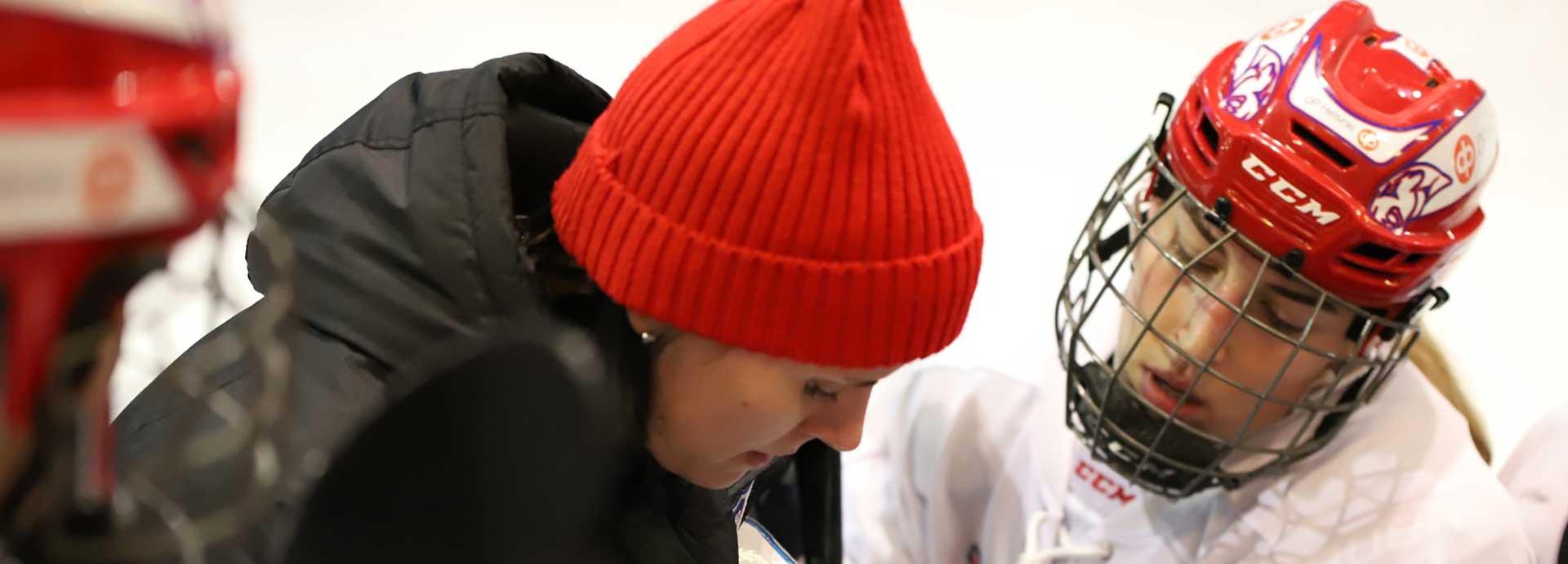

Last year, however, Niemi had the rare experience of sharing the perspective from both sides. When Stadin Gimmat was still playing in the second-tier series and looking for a chance to rise to the big leagues, which they eventually did, Niemi had to pull her skates on and join the team to fill the void left by injured players.

In doing this, she had to rely on her assistant coaches a lot at the time, because seeing the big picture and controlling her emotions was much harder while she was on the ice herself. Niemi also hoped that her experience would teach the team a valuable lesson in teamwork, with both her and her assistant coaches pulling a stunt to give the team a crash course in receiving criticism positively.

“One time, I had played a bad game and told the assistant to be absolutely brutal to me in the locker room. I didn’t want any special treatment, and I wanted the players to see that,” she explains.

Togetherness is key

Speaking of special treatment, in the mainly Russian KHL league, it’s very common for teams to separate their players into two different practice squads based on whether they are natives or international players. The team plays together only during actual games. Pikkarainen disagrees with this approach.

“Separating a team by nationality wouldn’t be possible here. In addition to time on the ice, we have a lot of sideline activities together as a team. You can see that, for example, American players haven’t become accustomed to that at all before they come here. But it’s the way we do it,” he explains.

Both Pikkarainen and Niemi should know. Pikkarainen has played and coached hockey teams during his entire career in Finland, while Niemi has also played in the US and coached in China. She adds that this togetherness and two-way interaction between coach and player is much more valued here in Finland than in eastern hockey.

“What makes HIFK a unique team is that everyone gets to be themselves. We have common values, but there are players born in four different decades, and everyone helps each other out. It’s all one big family,” says Niemi.