Sentinel-6 is in low Earth orbit accurately measuring sea levels, wind speed, and even wave height. This latest ocean-monitoring satellite has a vital role to play in understanding climate change and its impact on the maritime economy.

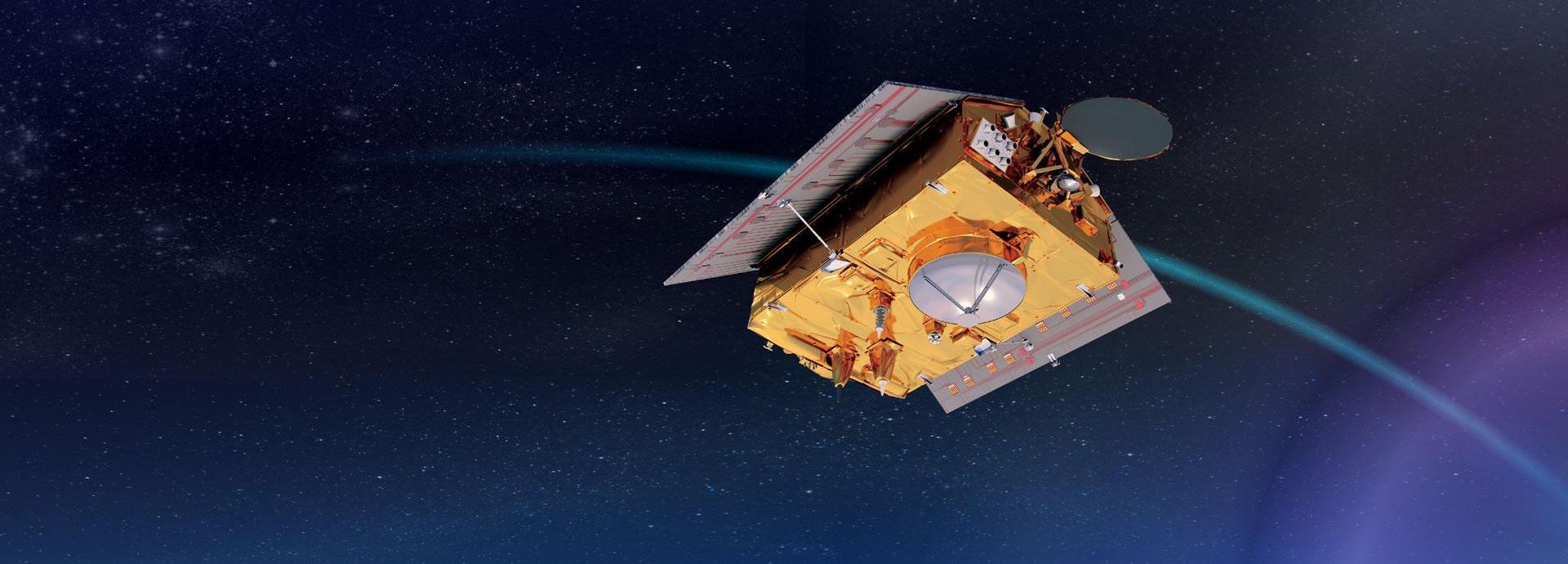

The Copernicus Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich ocean-monitoring satellite is currently orbiting the planet at an altitude of 1,336 km. Its primary mission is high-precision ocean altimetry, providing valuable information about sea surface topography, including sea level and significant wave height.

Launched in November 2020, it is the latest advanced technology to play an extremely important role in monitoring and preparing for the effects of climate change, specifically sea-level rise. Data gathered by the satellite also will be incorporated into meteorological models, which can help improve safety and efficiency in the maritime industry.

Improved understanding of the oceans

While NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) are sharing the multi-million-euro cost of the 10-year mission, data from Sentinel-6 is being collected and handled by the European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (EUMETSAT).

Principally an ocean-focused mission, the revolutionary technology will deliver the most accurate source of observations of sea surface height, mean sea level, wind speed, wave height, and ocean circulation, until at least 2030. Some of the measurements will be achieved through the use of electromagnetic waves emitted from the satellite, specifically radio wave pulses bouncing off the ocean surface and capturing their echo.

“Depending on the obstacles, the Electromyography or EMG wave behaves in different ways. For example, you can precisely measure the time it takes for the energy to come back, which can then be used to map the mean sea level or to extrapolate the moving ocean surface. From this, you can then infer the strength of the wind,” explains Paolo Ruti, chief scientist at EUMETSAT.

He adds that satellites like Sentinel-6 also provide data about ocean topography, being the equivalent of surface pressure in the atmosphere, and even ocean currents. This data can be fed into mathematical models to predict what will happen tomorrow – or in two weeks’ time.

“This information is important if you want to better understand how ocean currents could spread an oil spill or to where a ship in distress may have drifted,” Ruti says.

Other than satellites, there is no reliable way of systematically monitoring wind speeds or wave heights out in the ocean, which is one method of determining whether there are dangerously high waves that could impact shipping.

“You do not want to run a huge tanker through a wave height of 8-10 metres, so this data can be used as a warning and as a quality indicator,” adds Remko Scharroo, Sentinel-6’s project scientist.

With radar altimetry, ocean dynamics and global currents can be tracked and incorporated into ocean and meteorological models that can help with ship routing.

“For example, there can be eddies with diameters of around 200 km in the Gulf Stream. If a ship runs against the flow, then it expends more energy and takes more time. With a simple course correction, you can go with the flow,” adds Scharroo.

Regional and global sea-level changes

The Copernicus Sentinel-6 mission will extend the unique record of measuring sea-level rise that began in 1992 with the TOPEX/Poseidon mission (1992-2006). Since measurements began, the mean sea level has risen by about 3.2 mm per year over the past 27 years, but this increase is not uniform and tends to vary over time and in different regions.

“Having a full monitoring of the planet means that you can see that the sea-level rise has been average in some oceans, but it has also been up to 10-20 cm in some regions. Satellites give an overall picture and show the regional difference; it isn’t just the one number that you apply everywhere,” says Ruti, adding that while the overall trend is positive sometimes fluctuations from year to year can be negative.

Climate change deniers have used negative year-by-year variations to argue their case, but Ruti says that it is thanks to continuous satellite monitoring that these interannual variabilities are now understood. He quotes El Niño, a climate phenonmenon that occurs when the surface water in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean become unusually warm, as an example.

“For instance, El Niño is changing both the temperature of the ocean and rainfall patterns, meaning that less water falls into the ocean and more falls onto the land, which is then retained. The regional number is important for decision makers who are planning to implement protection measures against rising sea levels," says Scharroo.

“They want to know the current rate and maybe whether there will be an acceleration or a change, so they can build a flood defence that will last for 100 years and not be obsolete too soon. For that, you need accurate figures,” he adds.

A continuous need for measurement

When monitoring climate change, it is particularly important for scientists to know how much meltwater is coming from glaciers and the two poles. While there are specialised satellites in orbit providing that data, Ruti doesn’t think it is enough.

“The Arctic is a place that we don't observe as much as it deserves, but EUMETSAT and ESA are working to remedy that in future missions,” he says.

While the payloads for those missions is to be confirmed, the speed at which technological developments are being made is accelerating.

“You can read papers in scientific journals from just eight years ago saying that that a specific technology was unfeasible to be used in the specific setting of small satellites. Today, you have that same technology flying in space,” Ruti laughs.

Scharroo adds that Sentinel-6 is so forward looking that it has the capability to evolve its products further to make them even more accurate.

Ruti emphasizes that these missions are not just explorative, like going to the Moon once or twice. “We manage an operational system of which EUMETSAT is at the forefront. Our strength is that we measure 24/7 every year, which underscores the continuous need for measurements,” he adds.

Simply, their work is vital in understanding the role of the oceans in climate change.

Did you like this? Subscribe to Insights updates!

Once every six weeks, you will get the top picks – the latest and the greatest pieces – from this Insights channel by email.