Ivory Coast aims to achieve universal energy access by 2025 and triple its generation capacity by 2030. Find out how its public-private energy model can help the country achieve its ambitious energy targets.

Ivory Coast is on an economic roll: since 2011, GDP growth has averaged 8% per year making it not just one of the most dynamic countries in sub-Saharan Africa, but the world. With the economy and energy demand booming, the Ivorian government has put the energy sector at the top of its agenda.

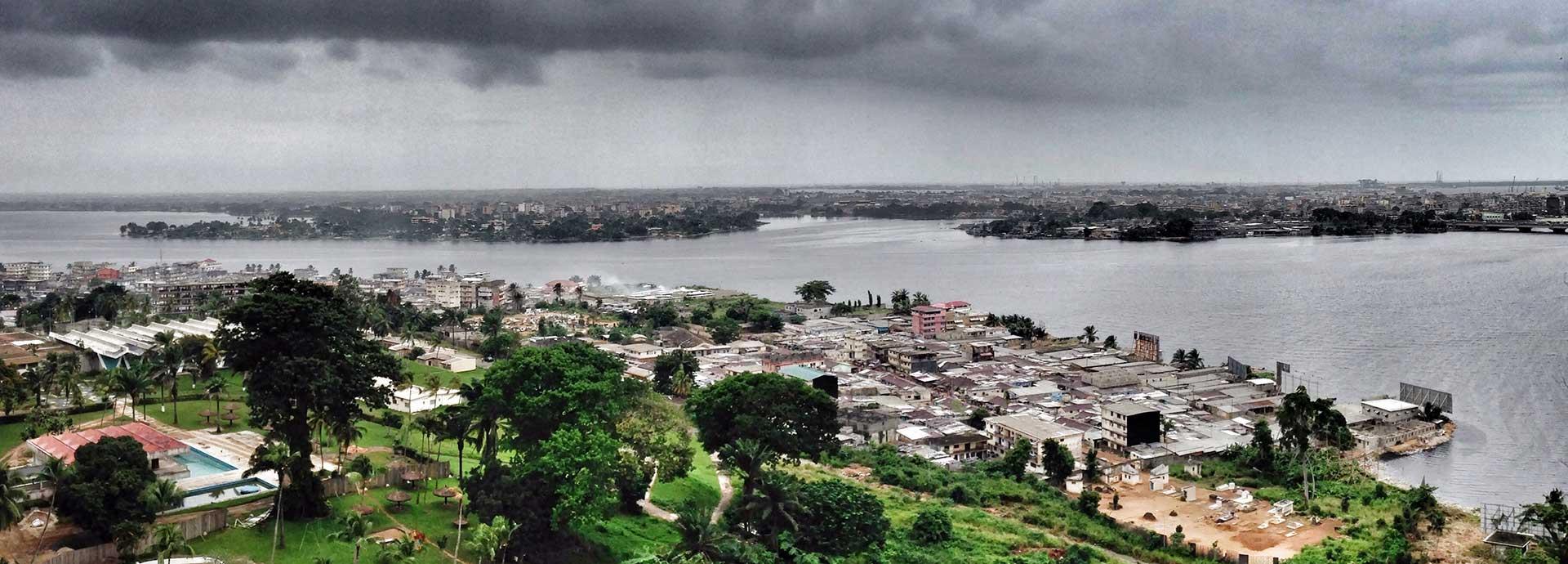

This is critical because, despite a thriving economy, the spoils of growth have not been equally shared. Three in five Ivorians have access to energy, but there is a vast discrepancy between urban dwellers (80%) and rural citizens (37%), with the rural north even less connected than their southern compatriots.

With almost half of the country below the poverty line, the high upfront connection costs to the national grid remain prohibitive for many. That’s not all. For those connected, the grid – which transmits through a 5,000 km network of high-voltage power – contains outdated systems that has led to energy losses of around 22%.

Ambitious plans for the future

So how does the government plan to remedy these issues and improve the sector? Through public-private partnerships. As the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to open up its energy sector to IPPs, it’s no surprise that currently 55% of its production comes from three private companies: Ciprel (556MW), Azito Energie (440MW) and Aggreko (210MW).

In October 2019, the Minister for Energy, Abdourahamné Cissé, told the Ivorian parliament about the success of the PEPT (Programme Électricité Pour Tous) project, which would achieve electrification rates of ‘80% by the end of 2020 and 100% by the end of 2025’. The programme, which is a partnership with the public-private Ivory Coast Electricity Company (CIE), aims to electrify all villages and towns with more than 500 inhabitants through a combination of off-grid and on-grid projects. For example, CIE has introduced tariffs as low as 1,000 CFA (EUR 1.5) so the least well-off can access the grid, while off-grid villages are benefiting from solar home kits and mini-grids, further enhancing the reach of electricity supply.

The government also aims to triple power production to 6,600 MW by 2030, mostly by using IPPs. For instance, Azito recently received funds to increase one of its plants from 253 MW to 700 MW, while a deal to build a 390 MW plant named Atinkou (or Ciprel 5) was signed in December 2018 with Ciprel. The use of IPPs shows no sign of slowing down, as when signing the deal, Cissé announced the “State’s ambition to strengthen the country’s electricity production capacity through new units operated by experienced private partners.”

Leveraging the public-private model

Ivory Coast’s engagement with private energy companies is not unique to the region. In fact, public-private partnerships are common across West Africa as they are equally popular with governments and private companies. According to Cyndo Obre, Project Development Manager at Wärtsilä Energy Business, “governments prefer such partnerships as you have a private company installing a plant and investing instead of you. Private sector intervention reduces and optimises the use of the state's financial resources, which can then be used for other equally important uses such as health or education.”

“Private companies like it for the same reason. Some projects are not financeable in the private sector as the risk is too strong or the return isn’t high enough for the risk taken. In the public-private partnership model, they can share the risk.”

While the Ivorian government has shown a preference for using the same private companies to expand their thermal and hydroelectric production, it also wants to increase its share of other renewables excluding hydro-power, such as biomass and solar, to 16% by 2030.

“Their ideal situation in 2030 is hydro-power, solar, biomass and flexible thermal,” says Obre.“For that, the government needs the flexibility that Wärtsilä’s engines provide as well as our storage capacity.” Acknowledging that Ivory Coast’s “biggest challenge is changing the energy mix,” Obre states that “until now they have known only turbines and hydro, but the growth of renewable energy such as solar will require more flexible capacity to complement the hydro in balancing the intermittency of renewables and providing grid services. Load following, fast start reserve and frequency regulation will be needed to maintain a stable grid. The turbines don’t have that flexibility, but Wärtsilä’s technology does.”

With the 2030 Energy Plan identifying 66 projects that will require private investment, the door is open for new private partners to stake their claim.

Did you like this? Subscribe to Insights updates!

Once every six weeks, you will get the top picks – the latest and the greatest pieces – from this Insights channel by email.