This year will see the first LNG-fuelled cruise ships come into service, and there are many more on order. Find out how Wärtsilä LNG solutions are playing a key role in meeting the industry’s high demands for space efficiency, safety and sustainability.

Very few still see LNG as a novelty and there is nothing new about a cruise ship. But until this year the two have never been combined.

This is about to change. In December, Carnival Cruise Line took delivery of AIDAnova, the first LNG-powered cruise ship. It will also put its second LNG vessel, the Costa Smeralda, into operation this summer. There are now about 20 new LNG-fuelled cruise ships on order, with all the major cruise companies – Carnival, MSC, Disney, Royal Caribbean, and TUI – betting big on the technology.

“We are talking about 50% of the normal order book for cruise ships in a year,” says Piero Zoglia, who leads the business development team for Wärtsilä's marine LNG business. “All the players are focusing 50%

on LNG fuel.”

The tipping point

Zoglia believes the arrival of cruise operators marks the tipping point for the fuel, as port operators and fuel suppliers will now be forced to extend bunkering facilities in dozens of new ports.

LNG has, in the past, been seen as suitable for ships on repetitive routes in seas with strict emissions controls, and not for vessels like cruise ships, which can be sent to another hemisphere at short notice. But improving bunkering availability, and the arrival of the first global sulphur cap next year, has made the fuel look more attractive. Vessels running on heavy fuel oil now need to install scrubber systems or pay a premium for low sulphur fuel, improving the economics of LNG.

When France's Compagnie du Ponant ordered Le Commandant Charcot, a specialist ship which will take sightseers on luxury expeditions to the North Pole, around Greenland, through the Bering Straits and to the penguin colonies of Antarctica, it opted for Wärtsilä's LNG dual-fuel engines.

“They are sailing in the North Sea and the Baltic Sea and that's a nitrogen oxide emission control area (NECA), so they have two options: low sulphur MDO or LNG,” says Zoglia. “The fuel price is attractive, and you also save on maintenance

costs because the engines are running on cleaner fuel.” IMO has committed to developing a ban on HFO, thereby making it no longer a realistic option for new projects in Arctic cruise.

Le Commandant Charcot. PHOTO: PONANT - STIRLING DESIGN INTERNATIONAL

Towards clean alternatives

But economics was not the only or even the main driver. The impacts of climate change are nowhere more visible than at the North and South Pole, where ships will be operating.

Public concern over environmental pollution affects the cruise industry more than any other sector. “They have to be clean. It is not only a matter of the rules and regulations but also a question of image,” explains Zoglia. “They have to go into ports at tourist destinations and in these ports, you don't want to have smoke emissions.”

With LNG there is no smoke at all. Switching from fuel oil to LNG cuts sulphur emissions to zero, particulate emissions by 98%, NOx emissions by 85%, and greenhouse gas emissions by a quarter. It should, therefore, be no surprise that the fuel is attractive.

Tailor-made solutions

The cruise ships currently on order are the first to be fuelled by LNG, meaning companies like Wärtsilä are having to work hard to meet entirely new demands.“It is very complex, very difficult, with very demanding customers,” says Zoglia. “There's not one project which is like what anyone has done before.”

LNG's lower fuel density means that an LNG vessel typically requires twice as much tank space as one fuelled by diesel. Standard cylindrical tanks compound the problem, as they fill only about 40% of the rectangular space needed to house them.

This is a particular problem for cruise vessels, Zoglia points out: “In a cruise ship, every cubic metre you lose might be a cabin you give away.”

Wärtsilä worked with the French engineering company GTT to develop a membrane tank for the icebreaking cruise ship Le Commandant Charcot, which could be fitted to the shape of the hull. As much as 75% of the

space was used for fuel storage. It is a technology which has been used on LNG carriers but never before on a cruise vessel.

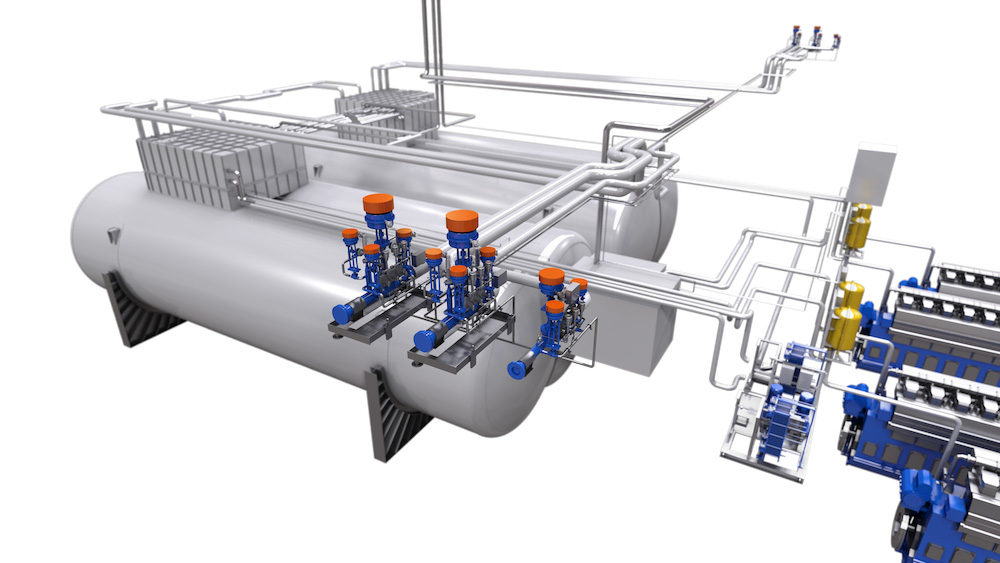

Wärtsilä’s Multi-Lobe LNGPac.

Safety first and foremost

On another project, Wärtsilä supplied Bilobe Type C tanks, which use 60% of the available space for gas storage. Again, Wärtsilä is the first to supply this technology to a cruise ship. Because Bilobe tanks are pressure tanks made of stainless steel, they are one of the best technologies from a safety perspective.

Cruise ships have some of the strictest safety standards in the industry, and Wärtsilä has built triple redundancy into the LNG systems it has supplied.

This means having two LNG tank systems working in parallel and ready to take full control in case of a single failure. Even if both fail, the diesel used as pilot fuel in the engines is stored in sufficient quantities, so that the engines can switch to diesel and bring the vessel back to the nearest port.

“For a cruise ship that's particularly important because passengers don’t care if there is a technical problem on board: they have paid for the ticket and the cruise must go on,” says Zoglia. “Safety and reliability are of utmost importance on board these ships. They are the top priorities.”

Every year between now and 2026 (at least) will see new LNG-fuelled cruise ships hit the market, and their operators lobby hard to bring bunkering to all their key ports. At the same time, oil and gas companies will order LNG bunkering ships which will make LNG refuelling much more flexible.

With the arrival of the cruise giants, it is time to stop talking about LNG's 'chicken-and-egg conundrum'. The fuel has come of age.