In the year 1954, Arno Saraste, Managing Director of Wärtsilä’s Vaasa Factory, made a decision that would have a significant impact on the company’s future: this was to design and develop Wärtsilä’s first diesel engine. Before this, Wärtsilä had only been producing engines under license from the Krupp Corporation, Nohab and Sulzer. Developing an engine from scratch is not an easy task. Which is why Saraste roped in a talented graduate engineer (MSc Eng), Wilmer Wahlstedt to carry out the task. The rest is history.

“Saraste gave a call to Wahlstedt and asked him to Vaasa to lead the development project of the new auxiliary diesel engine and Wilmer responded positively,” recalls Matti Kleimola, an ex-Wärtsilian, who was a chief of engine design group and later a Head of Product Development at Wärtsilä’s diesel engine division from 1974 to 1983.

From the very beginning, it was clear that Wahlstedt was the right man for the job. He was experienced in designing diesel engines at Wärtsilä’s Turku Shipyard and had also written his master’s thesis on the design and operation of diesel engines. “He was very motivated and worked long days to get the first diesel engine design, the Wärtsilä Vasa 14, out of the door,” adds Kleimola.

A design to stand the test of time

The completed Wärtsilä Vasa 14 – a three-cylinder auxiliary engine – was started for the first time in June 1959.

“It was an important step for Wärtsilä. But I also have to say, that it was a right move to start the engine development from auxiliary engines and not from main engines especially since the company was not, at that time, known as an engine maker. Shipowners prefer to choose familiar main engine brands. Seldom do they accept prototypes or newer brands. But when it comes to auxiliary engines, customer preferences were more fluid,” says Kleimola.

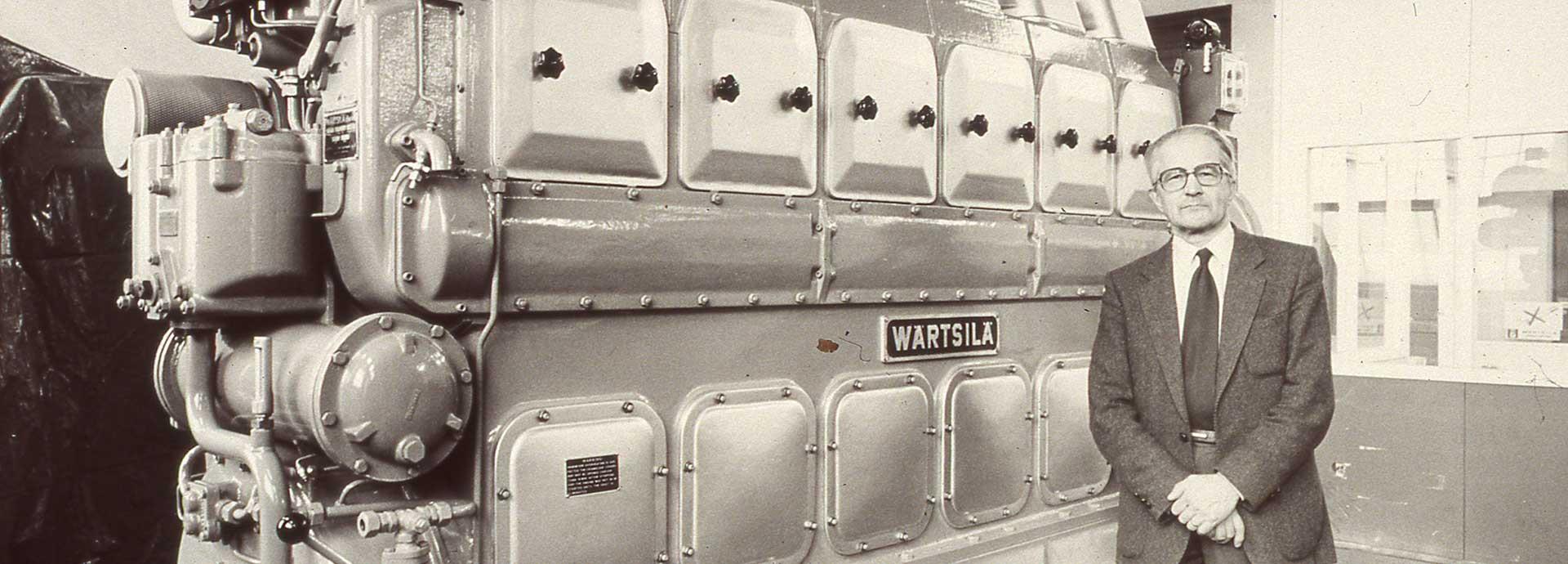

The first commercial Vasa 14 diesel engines were sold to Silja Line’s car ferry, the m/s Skandia. In order to ensure quick maintenance, arrangements were made to build for each genset, a bed that had a lid on a car deck that could be opened in case of engine damage. An extra engine was stored in Turku, but thanks to the reliability of the installed engines, there wasn’t any need to use it as a spare. Eventually, this spare engine was moved to the lobby of Wärtsilä’s factory in Vaasa where it can still be seen today, a testament to the company’s history of innovation and game-changing design.

“The Vasa 14 engine was definitely proof of good engineering. Later in the 60s, the Vasa 14 was developed further, with a focus on more power and better performance, with turbocharged and intercooled versions, named the Vasa 24T and the Vasa 24TS. So it’s not a surprise that people were interested in buying these engines,” explains Kleimola. “Wahlstedt went the extra mile by coaching the selling engineers to thoroughly understand the engine philosophy, its design principles, performance levels and service requirements. With that knowledge, they could answer the trickiest questions and showcase the full potential of the engine.”

Wahlstedt also recruited a lot of skilled students from the University of Applied Sciences to help with the project, with everyone working together as a team to complete the engine’s design. “They were eager and motivated to develop the best diesel engines in the world,” explains Kleimola.

The first in a series

The Vasa 14 was just the beginning for Wärtsilä. Using it as a template, the company improved upon its strengths and released the Wärtsilä Vasa 22 auxiliary engine in 1974, followed soon after by the Wärtsilä Vasa 32 main engine. The latter was also the first engine project at Wärtsilä helmed by Kleimola. “It was a very challenging project which required a lot from my young team, which had about 20 people onboard for R&D. But everyone did an excellent job,” recalls Kleimola. “To ensure that the development process runs smoothly we arranged monthly design review meetings together with marketing, production and service professionals to get their feedback. Straightforward and agile cooperation with the production department helped speed up the manufacturing period of the test engine.”

Wahlstedt, who had retired before Kleimola joined, showed interest in being part of the engine’s design process, taking part in the initial meetings. CAD/CAM technology had not yet been developed or was not available at that time. Thus, most of the engineering calculations were made by slide rules and by first-generation electronic pocket calculators. Heavy and cumbersome Finite Element Calculation methods were used to help in the design work of the engine’s main components.

“Wahlstedt created a great documenting system as well: all the information related to a specific topic from the meeting notes to articles, patents and drawings could be found from a folder named after that topic. That system was fantastic, and it helped us a lot when we were developing the Vasa 32 engine,” says Kleimola.

In 1976, production of the Vasa 32 engine kicked off. The engine type was in demand being the smallest heavy fuel engine on the market. Feedback was good, even though initial teething problems were reported. Following Wärtsilä’s cue, some competitors eventually started production on engines of a similar size.

“Our first engines went to Japan. Vasa 32 engines were among the first European engines ever delivered to Japanese ship markets. Before this, all the shipyards in Japan had been using only Japanese engines or engines made under license in Japan. Japan was a leading ship maker in the world that time,” explains Kleimola.

The first six engines were used in two reefer ships that were used in transporting vegetables and fruits between Australia and Japan, an important task since any delays or engine breakdowns would have resulted in the cargo being ruined. To safeguard against this, Wärtsilä deployed own service engineers on these ships for a period of six months to monitor the equipment and ensure that everything was ship-shape. No major problems occurred, and all parties were pleased by the engines’ performance.

New decades, new engines

Wärtsilä’s remarkable success with its engines continues down the decades. While each successive engine design was more technologically advanced than its predecessors, the basic principles behind the Vasa 14 (24) continued to influence the design process, as seen in the launch of the Wärtsilä 46 engine in 1987, Wärtsilä 20 in 1993, the next generation of the Wärtsilä 32 in 1995, the Wärtsilä 64 in 1999, the next generation of Wärtsilä 46 in 2004 and the Wärtsilä 31 in 2015.

Kleimola, who had left the company to work in Helsinki University of Technology as the Professor of Machine Design, returned to Wärtsilä as Chief Technology Officer and witnessed the evolution in engine design first-hand.

“Even when I was not working at Wärtsilä, I had been following development work closely,” he says. “Obviously the company had changed a lot in 20 years but many of the people I knew were still working at Wärtsilä and were using the experiences they had gained in designing the first of Wärtsilä’s engines as a basis for new models.”

When asked to compare Wärtsilä’s very first diesel engine Vasa 14 to the Wärtsilä 31, the world’s most efficient 4-stroke diesel engine, Kleimola is quick to point out that technological advances made in the decades separating the two make any such comparison unfair.

However, he does have an opinion on the matter. “If we compare the development processes or final results of Vasa 14 and Wärtsilä 31, one thing we can surely say is that both of them were top-class.”

Did you like this? Subscribe to Insights updates!

Once every six weeks, you will get the top picks – the latest and the greatest pieces – from this Insights channel by email.