Wärtsilä has always been quick to adopt new technology. However, its trailblazing role is not based on technological superiority as much as on a superior attitude that has allowed the Group to take its future into its own hands and create its own success.

Without courage and the right attitude you have nothing

From the perspective of technology, Wärtsilä’s development over the past 60 years has certainly been diverse. With this in mind, we should start by going back to the 1960s, when the old conglomerate was producing everything from toilets to locks, ships, washing machines and caravans.

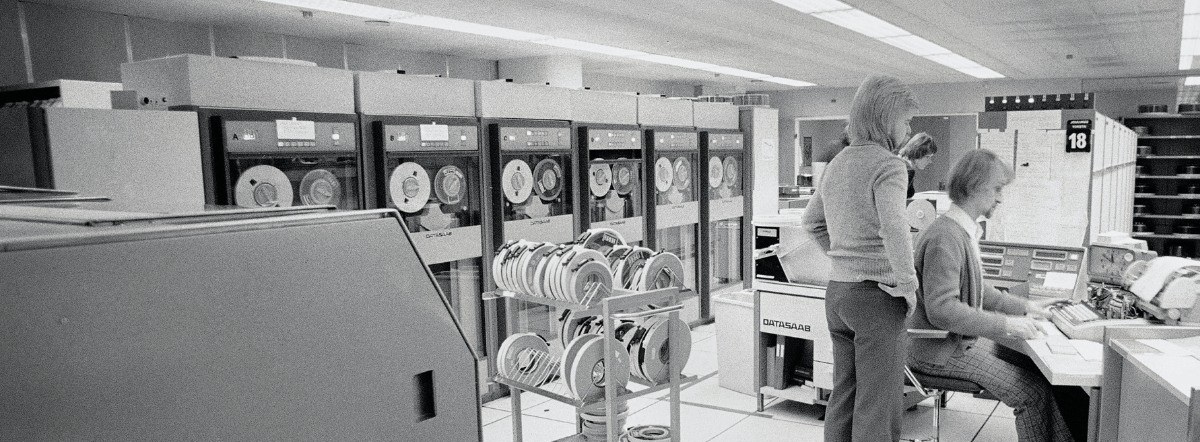

The Group has always been quick to adopt new technology and come up with innovations of its own. The first computer arrived on Finland’s shores in 1961, at the Helsinki University of Technology. Wärtsilä booted up its first computer just two years later and even established an IT department at the Helsinki shipyard. Another two years on, the company was using a computer-based system for cutting steel.

Wärtsilä became the first company in the entire world to have the ability to go from the engineering stage directly to the production machines without an intermediate stage involving the traditional drawing boards. This reduced the time spent on steel engineering, which is a major part of shipbuilding, by 90 per cent.

Back then, environmental considerations were an economic issue. They represented a way to improve efficiency, extend life cycles and thereby reduce costs, rather than being a starting point for engineering, which they only emerged as in the early 2000s.

Environmental ship systems and unpickable locks

The Finlandia car ferry delivered in 1967 was already equipped with a waste management system. Until then, all waste had simply been tossed overboard, including paperboard and glass. Thanks to the development efforts of Wärtsilä’s young engineers, the Helsinki shipyard won the Shipyard of the Year award for its new waste management system.

For MS Song of Norway, a cruise ship completed in 1970, Wärtsilä’s key innovation was a vacuum toilet that reduced water consumption from 20 litres per flush to one litre. The invention was later utilised by Sanitec, which was established as a subsidiary of Wärtsilä in 1990 and subsequently sold to a Germany-based private equity firm after the turn of the century.

Another major 1970s innovation that deserves mention is the lock developed by Abloy Oy, which was part of Wärtsilä Group at the time. Abloy’s subsequent merger with Assa became one of the most profitable pieces of business in Wärtsilä’s entire history, and the success story of Abloy locks has continued into the 21st century under the Assa Abloy banner.

The new age in shipbuilding

In addition to toilets and locks, Wärtsilä was also ahead of its time when it came to modular construction. The shipbuilding process was turned on its head at the turn of the 1960s–70s. Until that time, the approach had been to first build the hull and only then build the cabins and other interior elements inside the confined spaces of the ship. The new method was to design the steel hull according to a specific cabin layout. Cabins were built separately, according to detailed specifications, at a factory established in Piikkiö for that purpose.

This made it possible to build the cabins at the same time as the ship’s hull – a prime example of out-of-the-box thinking that has since become the global standard in all types of construction. This was Wärtsilä at its best.

Another innovation that was well ahead of its time was a prototype of an entirely automated production plant for Sanitec in Sweden, including a fully robotic production line, although Sanitec’s new owner would later discontinue the plant’s operations in the 2000s.

Pioneering icebreakers

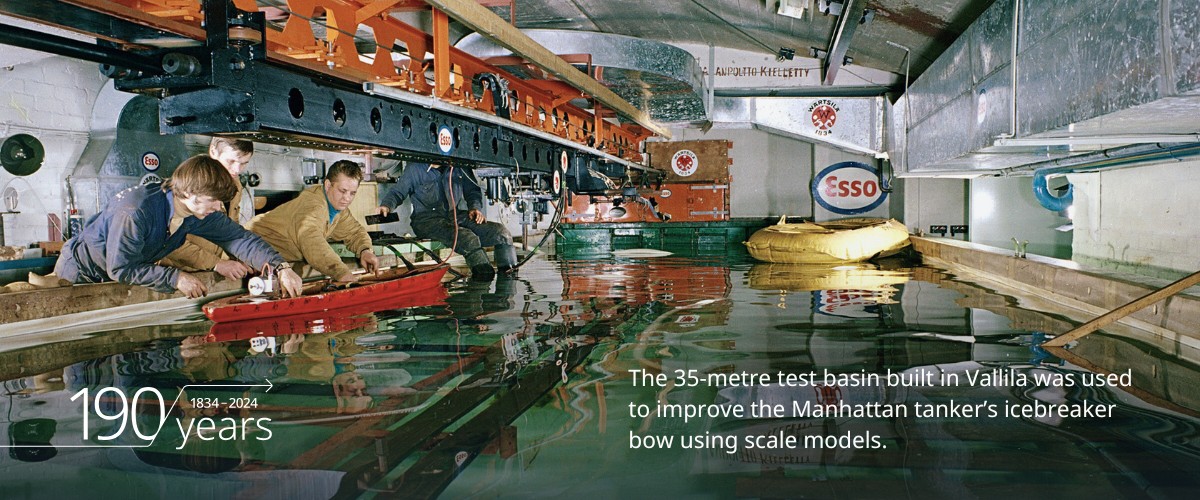

Icebreakers are a chapter unto themselves. In 1968, Exxon found a vast oil field in Alaska. The problem was transporting the oil to the markets. The Exxon-owned tanker SS Manhattan had to be converted into an icebreaker, and Wärtsilä won the contract. The company now had a Manhattan Project of its own.

In 1969, a 35-metre ice test basin was built for the project in Helsinki’s Vallila district, funded by the Americans. Based on the designs developed in Vallila, the tanker was subsequently reinforced and extended and its bow was reshaped. The project was a success and SS Manhattan became the first commercial vessel to transit the Northwest Passage.

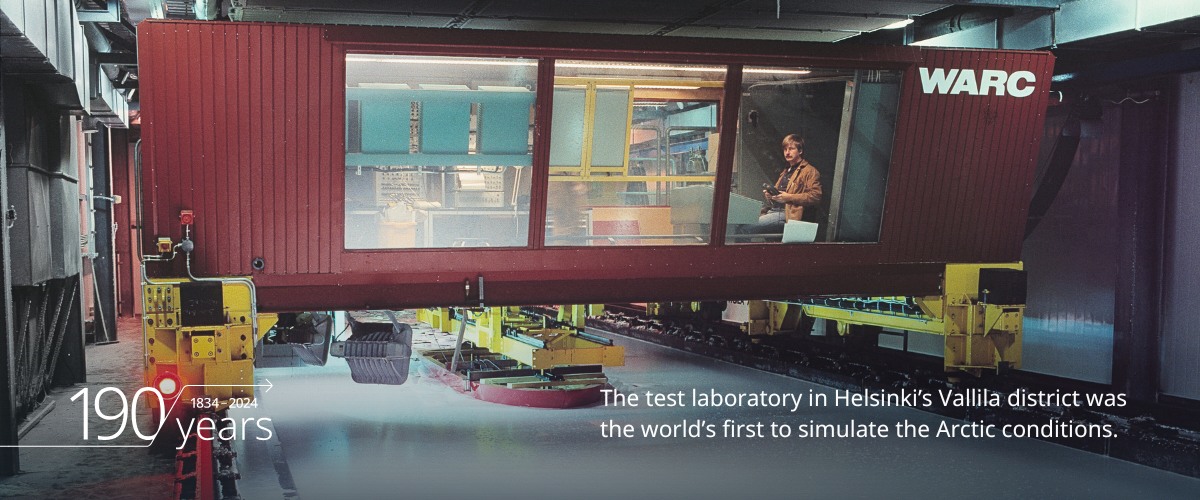

For Wärtsilä, the project’s significance went beyond its price tag, which was around EUR 300 million in today’s money. It meant that Helsinki was now home to a state-of-the-art ice laboratory along with the empirical data and methodology that came with it. This capital was put to good use. One milestone was Urho, commissioned in 1975, representing the world’s first icebreaker that had been exclusively tested using an artificial water basin.

Inspired by the SS Manhattan project, Wärtsilä’s new Arctic research centre was inaugurated in 1982 in Helsinki’s Arabia district. Today, Helsinki’s icebreaker research and testing tradition lives on in the form of Aker Arctic, which was established in Vuosaari in 2007–2008.

These examples are a testament to Wärtsilä's enduring legacy — a company that has not only stood the test of time but constantly reimagines what is possible.